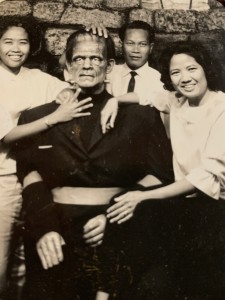

- Shelly’s monster is a timeless pop culture icon–vintage photo was taken from the Movieland Wax Museum, Buena Park, California (circa 1950s)

Preface: Since the inception of the Film Criticism and Theory course, there were always a few students who decided to write an argumentative research paper exploring Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein through gender (feminist) theory, genre theory, or adaptation theory while applying it to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner or Alex Garland’s Ex Machina. After countless discussions on how to guide their argument as well research, the task became a challenging feat for both students and myself. Shelly’s literary masterpiece that ultimately became a leading pioneer in the science fiction genre can also be credited to providing a narrative basis to another intellectual medium that came more than a century later, that is, the motion picture or cinema. Cinema continues to offer a new “lens” on the genre of science fiction—whether it be an exploration on horror, gender, Marxism, capitalism, technology, religion (Christianity in particular), and so on—-all of which are illustrated in Scott and Garland’s provocative cinematic narratives. Their films along with Shelly’s literary piece have led to complex philosophical discussions that are not always simple and lucid. As a result, I decided to sort out the discussions I had with my students with more clarity in all three works. The task took an entire summer (beginning June 9, 2019), almost half a school year to complete. Now I understand my students’ arduous (and sometimes painful) journey—-yet it was one that I greatly admired, considering they only had less than a semester to complete their research. Therefore, I dedicate this comprehensive piece to the young film critics who have challenged themselves to delve into the convoluted yet fascinating world of the science fiction genre, particularly in an everchanging and progressive art medium—-cinema.

April 8, 2020 (completed in the year of the Great Pandemic)

Shelley’s Second Sex and the Science of Woman

Centuries after Mary Shelly’s 1818 release of Frankenstein the novel continues to raise provocative issues on the creation of a second sex as a necessity for man—much to the likeness of an Adam yearning for his Eve. After reading John Milton’s Paradise Lost, the monster laments to his creator, Victor Frankenstein, that there was “no Eve [to] soothe my sorrows nor shared my thoughts” (Shelley 116). As a result, the monster asks his creator to create a companion for him in which he describes to be a “creature of another sex” (Shelley 132). The other sex will prevent him from sinister acts. The “love of another will destroy the cause of [his] crimes;” the monster “shall become a thing of whose existence everyone will be ignorant;” and his “evil passions will have fled, for [he] shall meet with sympathy” (Shelley 132-133). And with a woman next to him, the promise of order will be restored. Or will it? There are two different views of femininity inFrankenstein, especially from Victor and the monster, one being a soothing companion and the other being another uncontrollable monster respectively. Because of these polarizing views of a woman’s role, Shelley’s work explores and challenges man’s idea of what constitute the nature of femininity from a scientific standpoint.

From Frankenstein to Blade Runner[1] and Ex Machina

Shelley’s science fiction masterpiece sets the groundwork for the manufactured woman trope—particularly its issues on the politics of feminism in a modern world. Although Frankenstein reneges on his promise of creating another monster, this creation of the “other” sex compels us to ponder the type of woman Victor Frankenstein would have created. We are only limited to the knowledge that the monster’s female counterpart would have the capabilities of quelling the monster’s dangerous compulsions. The female AI becomes a provocative trope in science fiction narratives (especially in cinema), which coincides with Shelley’s influential theme of technology as an invasion or intruder to modern life—but this time the disruption is in the dynamic interplay between the sexes, breaking down traditional sexual codes of behavior such as man’s narcissistic God-like endeavors to create the ideal woman left to his imaginations—all of which signify his flawed and unrealistic attempt to cement the socially prescribed gender roles of the perfect female prototype in the form of a fembot (the docile and subservient beauty) and the dominant male (as her creator and master). The fembot or AI, as with all technology, ironically becomes a threat to man’s dominant existence, especially when the AI takes on the form of a femme fatale but in actuality, the fatales (or rather fatalism) reside in man’s flawed technological ambition spurred by his own projection of the “yes master” female automaton. The conflict between the “counterfeit” woman and the narcissistic mad scientist serves as an allegory to more progressive male-female dynamics reminiscent of Shelley’s embracing of egalitarian roles between the sexes echoed from her mother’s most distinguished 1792 feminist work, The Vindication of Rights of Woman by Mary Wollstonecraft. Wollstonecraft refutes the idea that “woman was created for man” (110). In addition, the creation story where Adam’s rib is used to help create Eve is an absurd justification for man to “[find] it convenient to exert his strength to subjugate his [female] companion” (Wollstonecraft 110).

Through the science fiction genre, Shelley’s Frankenstein attacks sexism in Frankenstein. Shelley presents a criticism of various female prototypes of the 1800s that can best be described as patriarchal. Although Shelley does not explicitly explore the female simulacrum or the female synthetic, she does offer a discussion on the varied prototypes of women in a patriarchal milieu during the wake of advanced scientific endeavors. Men are given power to “birth” humans, reducing women to martyrs and victims—or in some cases, their antithesis, such as crusaders or rebels, but they are considered an aberration frowned upon by a patriarchal society. These opposing female prototypes lend themselves to a discussion of female identity amid a patriarchal society. Elizabeth, the adopted cousin of Victor Frankenstein, was simply a patient fiancé to Victor Frankenstein who has put off marriage to her until he completes his second creation to fulfill his obligation to the monster. Because of her lowly origins, she eventually becomes the “silent, acquiescent replacement for Victor Frankenstein’s mother” and “a rational, if superhumanly patient female character” (Wright 108). Elizabeth is molded by her adopted parents as well as Victor Frankenstein: she was raised in an aristocratic family and groomed to be the wife of Victor Frankenstein, especially at the behest of Victor’s mother who dies later during his early adulthood. Her predetermined existence makes her devoid of any profound beliefs. She is one of the “female characters [who] are muted, redefined by the male characters who narrate them” (Wright 108). She eventually becomes the disposable fembot. When she is killed by Victor’s creation, her body is described to be a mangled doll. “She was there, lifeless and inanimate, thrown across the bed, her head hanging down and her pale and distorted features half covered by her hair. Everywhere I turn I see the same figure—her bloodless arms and relaxed from flung by the murderer on its bridal bier” (Shelley 169). Her “disposable” nature coincides with her female “mechanics.” As fembots are usually substitute for wives or female companions, Elizabeth is a substitute for a mother. Like a troubled mother, she is always expressing concern for his declining health due to being too engrossed in his studies and laboratory work. She is a fembot who dies even before the marriage is consummated, stripping her of the chance of conceiving a human. She is, metaphorically speaking, a synthetic woman—perfectly “designed” to comfort Victor when he gazes at her: “Her brow was clear and ample, her blue eyes cloudless, and her lips and the moulding of her face so expressive of sensibility and sweetness that none could behold her without looking on her as of a distinct species, a heaven-sent, and bearing a celestial stamp in all her features” (Shelley 20). She is a woman of subdued quality but good enough to provide him the comfort of companionship—but one that is short-lived as the monster destroys her.

However, the other female prototype, Safie, is considered the feminist in terms of the rebel or crusader. She is the love interest of Felix De Laceys, the son of one of the cottagers whom the monster has spent days observing. What makes Safie a foil to Elizabeth is that she “pursues physical, intellectual, romantic and spiritual liberty outside the literally patriarchal limits set by her father and his culture” (Cracium 94). Safie, who is part Turkish descent, abandons her religion and her father in order to create her own existence. She abhors xenophobia. Without qualms, she travels alone to be with her French lover, Felix. She represents the ideal educated woman with a voice more that specifically relates to Wollstonecraft’s “radical ideas about the rights of women to education and public agency,” which significantly “works against the male narrators” along “with their disastrous separation from the women in their lives” (Cracium 94).

When Victor destroys the female monster in fear that it might be harder to control, it is an allegorical representation of the female who might gain unprecedented intelligence, independence, and rebellious tendencies particularly against societal norms. All of these characteristics pose as challenges to her male counterparts. Thus, Shelley is critical of the female constraints stemming from male-centrism and male superiority. The father-creator and/or the authoritative patriarch’s “social and cultural design” of woman are mere reflection of man’s “dis-eased” with the educated, independent, and rebellious woman. Scientific ambition and narcissism perpetuate the creation of the subservient woman as opposed to the female dominant or the female independent. Through this, Shelley paves the way to an unorthodox feminist probe of womanness in the science fiction genre explicitly challenging cultural and social norms. She was, indeed, reflective of the current milieu and the milieus to come.

The idea of womanness comes under great scrutiny—especially if the woman demonstrates cognitive abilities that are more than what a man can handle. Victor refuses to create a companion for the monster because this so-called Eve “might become ten thousand times more malignant than her mate and delight, for its own sake, in murder and wretchedness” (Shelley 150). Victor’s apprehension not only raises questions of more chaos in the world, but it also becomes the political foundations when it comes to femininity, that is, the act and the purpose of being female from a social and/or cultural standpoint (as influenced by her feminist mother, Mary Wollstonecraft). From this, radical challenges to gender inequities that are present in the science fiction genre, especially through the exploration of female AIs who are created within the scope of traditional masculine ideals that naively glorify man’s perfect life with the perfect woman, are undeniably pushed to the forefront in Shelley’s work. The application of feminist theory in a science fiction genre can be perceived as revolutionary in its deconstruction of female AIs because it “raises doubts about ‘woman’ as an essential definitional category and it questions the distinction between being a woman and performing femininity” according to Veronica Hollinger’s critical essay, “Feminist theory and Science Fiction” (126). The science fiction genre has an ironic literary disposition since it is dubbed as “’literature of change,’” in spite of the fact that “it has been slow to recognize the historical contingency and cultural conventionality of many of our ideas about sexual identity and desire,” “gendered behavior,” and “the ‘natural’ roles of women and men” (Hollinger 126).

The genre itself has been widely perceived to be popular amongst males—written for males and read by males, thereby, catering to man’s fashioning of sociocultural gender coding where “knowledge, innovation, and even perception [are considered] masculine” and “’the passive object of exploration is described [to be] feminine’” (qtd. in Merrick). This is clearly illustrated in the 1938 story “Helen O’Loy” by Lester del Rey. “Helen O’Loy” was far from being modern or futuristic but rather Victorian-like in its depiction of femininity—docile, submissive, and without thought—much like Elizabeth, the waiting fiancé for Victor Frankenstein. The artificial woman, Helen O’Loy, is named after the beautiful Greek mortal. Helen, the fembot, becomes the domestic goddess and the loyal lover of one of her creators, Dave. The story epitomizes the ultimate science fiction romance that caters to a man’s fantasy—where man can easily make “adjustments” to a woman such as removing her memory coils (if the fembot is too emotional) or cutting out the adrenal pack to “restore” a woman to “normalcy” (so that the woman will be less combative, temperamental, or vocal.) The two main characters, Dave and Phil, scientists who have created varying models of fembots to suit their needs, have engaged in this type of superficial and archaic feminizing of woman. With Helen, she was considered the ultimate artificial female—a feminine artifice that was scientifically created. Her existence consists of the three criteria: “one part beauty, one part dream, one part science” (del Rey 49). From this, she became “a good cook” and “a genius, with all the good points of a woman and a mech combined” (49). They fawned over her like a well-made car and christened her with a feminine name—adding to her allure. The manufactured woman becomes machine-like. Anything that remains “broken” or not functioning well, according to a man’s idea of a well-made woman, must be “fixed.”

Man’s rejection of a woman’s natural drive for freedom and consciousness continues to resonate in other science fiction mediums—more specifically in cinema. The docility of a woman as an ogled sexual object and/or instrument of pleasure is explicit in a visual medium. By the very visual nature of a cinematic medium, the sexualized fembots is far more expressionistic within the science fiction genre in detailing man’s sexual fantasy. The visual pleasure of screening a science fiction narrative that exploits a woman’s sexual femininity is twofold. Because of this, it also invites feminist issues such as Laura Mulvey’s most notable feminist theory of the “Male Gaze” in her work “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” She asserts that the “male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female figure” and women’s “traditional exhibitionist role . . . are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness” (Mulvey 715). In essence, cinema provides an illusion of voyeurism, much like Hitchcock’s Psycho where the peeping Tom (i.e., Norman Bates) is not only the male character in the film but also the surrogate for male spectators. Male audiences identifying with the male gazing protagonists account for their symbiotic relationship as mutual participants in erotic voyeurism and female body fetishization.

With the fembot motif ubiquitous in the science fiction genre, two films offer a more revolutionary outlook on how female AIs are portrayed in a cinematic narrative. In other words, they offer a more progressive approach to the politics of sexual identity. The postmodern film of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) and the more recent film of the second millennium Alex Garland’s Ex Machina (2014) deconstruct the fembot prototype—as the so-called fatales engage in their own existential understanding of themselves rather than being dictated or programmed by their creators. From this, the “male gaze” takes on a new meaning—the gaze and the schematic projections that arise from it—become the very notion that lead to his demise. This gives rise to the new meaning of femme fatale where the fatale stems from man’s naïve, culturally coded, misogynistic, and chauvinistic perception of woman.

Scott and Garland push boundaries when it comes to femininity by exploring, reversing, and debunking the naïve notions of the role of man and woman (i.e., the prince and his princess, the hero and the damsel in distress, the creator and the created) that are found in the most basic narratives that elevates man as superior to woman or woman dependent on man. Both films are progressive in challenging gender prototypes by making the concept of the femme fatale a misnomer, especially within a science fiction context. The metaphor behind the science of woman draws emphasis on the paradoxical understanding of the female artificial intelligence. The intelligence is really a female natural inclination to assert free will, thereby, underscoring the intelligence as opposed to the artificial. The female AIs are cultural and social models who represent women who are independent from their oppressors, intuitive, free-willed, unconventional in traditional social and cultural gender codes, and most of all, very human in their drive for survival.

Dystopia, Disorder, and Science Fiction’s Multiplicities

Before examining the social and culture politics of female identity, it is important to examine how they are ideologically contextualized in a nuanced science fiction genre. The dangers of creating the manufactured human coincides with the disorder of the natural world, which is captured through Frankenstein’s mood and atmosphere through gothic (horror) conventions placed in a science fiction narrative—and such hybridization emphasize the unsettled and chaotic world that is also illustrated in both Blade Runner and Ex Machina. In Frankenstein, Shelley makes use of mood and atmosphere to underscore a world that is in disarray, which corresponds and reacts to Victor’s drive to tamper with the laws of natural creation—an obsession spurred by narcissism: “A new species would bless me as its creator and source; many happy and excellent natures would owe their being to me” (Shelley 39). He goes mad as a scientist who is remorseful for creating a monster he can no longer control, especially in the prevention in the death of his brother (William) and wife (Elizabeth). Before his verbal confrontation with the monster, Shelley sets up the literary mise en scène through sublime weather patterns such as a storm that disturbed the peacefulness of the mountainside: “The thunder sound of the avalanche or the cracking, reverberated along the mountains . . . which through the silent working of immutable laws, was ever and anon rent and torn” (Shelley 80). It is befitting to find the creature in the midst of nature’s chaotic wonderment in which Victor is actually mesmerized in spite of its frightening image:

“I perceived in the gloom a figure witch stole from behind a clump of trees near me; I stood fixed, gazing intently . . . A flash of lightning illuminated the object and discovered its shape plainly to me; its gigantic stature, and the deformity of its aspect, more hideous than belongs to humanity, instantly informed me that it was the wretch, the filthy demon to whom I had given life” (Shelley 60). This creature in the midst of nature going wild unifies the tumultuous atmosphere and unsettling mood. There is a sensation of fear that corresponds with nature’s doubling effect—the created and the creator both going out of control. From this, “Mary Shelley creates terror by recounting the story in such close detail as a prelude to describing what she sets as the preconditions of the ghost story” and “’one which would speak to the mysterious fears of our nature and awaken thrilling horror’” (qtd. in Wright 111). It “’would curdle the blood, and quicken the beatings of the heart’” (qtd. in Wright 111). This horror is not only about the physical horror that lurks but also the horror of technology intruding upon modern life. Man’s creation (initiated by his own intellectual ambition) becomes a threat to himself and humanity. Thus, man must fear his own intelligence—and the moral compromises that follow.

Blade Runner

The terror or horror is depicted in a dystopian world envisioned in Ridley Scott’s futuristic science fiction narrative Blade Runner, which takes place in 2019. Scott pulls together two genres, noir and science fiction, in which noir conventions are integrated in a science fiction narrative. Noir aesthetics are captured through mood and atmosphere. The film was released in 1982, a period that was well into the postmodernist movement—an intellectual mode of discourse that questions or rejects origins, truths, models, and meanings in various art mediums, including cinema. Through postmodern tenets, Blade Runner immerses itself in the politics of consumerism, commodity, humanness, technology, and morality. Through a postmodernist lens, there is subversion, irony (as a critical parody), and pastiche (with the intent to examine old conventions). Scott’s irony is his scathing portrayal of urban decay in spite of technological advancements. Classic Los Angeles, the city of dreams of being rich and famous, especially during the 1940s and 50s and the heyday of the noir genre, is now the antithesis of such “classic” ideal—at least from a postmodern standpoint. Los Angeles is a breeding ground of civil and moral unrest, particularly in 2019, where technology is supposed to make the world easier and economically promising. The iconography of sunny Los Angeles and its dream-starter promise is long forgotten.

Furthermore, “Ridley Scott has said that Blade Runner ‘is a film set forty years hence, made in the style of forty years ago,’ as “the story borrows liberally from the private-eye genre, via the film noirs of the 40s and 50s with “the alienated hero with a questionable moral compass, the femme fatale, the Los Angeles setting, the movement from high-class penthouses to lower-class dives: all of these are familiar—indeed, overfamiliar—trappings of noir” (Bukatman 20). Remnants of the past are infused or retrofitted, which is what most postmodernists would assert, in Scott’s futuristic dystopia. Deckard still wears the detective fedora hat and trench coat. Rachel, the sexy 1940s femme fatale, is wearing the dated dress suit of the period with the notable thick shoulder pads and a tightly wrapped pencil skirt.

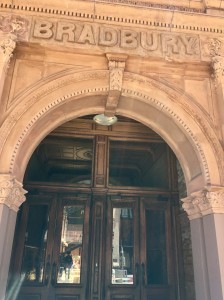

The iconic Bradbury Building remains erect with its wrought iron skeleton, but the building itself is lackluster, defunct, obsolete, and neglected. It is a world where the disparity between the rich and the poor are clearly demarcated. The Bradbury Building’s faded iconic stature is juxtaposed with Tyrell’s heaven-like penthouse. Tyrell is the creator and CEO of the Tyrell Corporation and lead manufacturer of androids or artificial intelligence known as replicants. His palace is far removed from the housing or working conditions of his employers who reside in the crime infested, overpopulated, dingy downtown Los Angeles. Symbolically, their lowly geography coincides with their socioeconomic status, the bottom of the corporate echelon. Blade Runner’s disorder is caused by corporate control through the use of advanced technology.

In Shelley’s Frankenstein, Victor laments about the disorder that he has caused since his creation symbolically takes place amid the tumult of a storm: “The thunder ceased, but the rain still continued, and the scene was enveloped in an impenetrable darkness. I revolved in my mind the events which I had until now sought to forget: the whole train of my progress towards the creation, the appearance of the work of my own hands alive at my bedside, its departure. Two years had now nearly elapsed since the night on which he first received life, and was this his first crime?” (Shelley 61). Unlike Shelley, Scott’s moral questions takes place in a decayed world—not caused by antiquation, but rather through the addition of technology—not only through the creation of a humanoid but also through the use of other forms of technology that aid in moral corruption. The immoral acts that stem from an ambitious God such as the implantation of AI’s memories derived from other humans, the life spans, and the emotional and physical human qualities are motivated by corporate control and greed—in this case, slave labor, their existential commodification, and the use of technology for corporate propaganda used to bolster consumerism.

More significantly, Scott’s pastiche is illustrated through his “pasting” of the noir genre within a science fiction backdrop, illustrating another tenant of postmodernism that rejects noir’s narrative modes in a conscientious dismantling of its forms and conventions in order to present a criticism of modern, high tech world. Typifying the noir genre, the narrative takes place at night in a dark Los Angeles (no longer sunny Los Angeles). The city is partially illuminated by the technological pollution. Scott’s dystopian world is underscored by his use of mood and atmosphere in a metropolitan Los Angeles, an eroding city, caught in a rapidly moving technological world and wrapped in the throes of aggressive capitalism and hyper-consumerism where “the state, in sf [science fiction] as in postmodernity, is replaced by the multinational corporation” (Butler 140). In a postmodern climate, there is information overload, inundating the consumer to existential ruin—socially, culturally, economically. “Postmodernist individual risk obliteration through . . . the saturation of the environment with images, messages and other attempts at communication” (Butler 142-143). As a result, “we no longer experience life from where we are, but from the intersections between us and other ‘individuals’ who are also under attack” stemming from “multi-channel T, the Internet, dozens of different permutations to choose from at the local coffee bar” (Butler 142-143). Deckard’s means of communications consists of real time television screen. Blimp advertisements roam the sky. Electronic billboards besiege Deckard in the communication chaos. In particular, the façades of the Los Angeles high-rise buildings are electronic canvases for aggressive international corporate advertisements—more specifically, from Japan. “In the film’s intricate urbanism, the iconographies of science fiction and noir overlap” (Bukatman 50).

The film was released in 1982, a period during President Ronald Reagan’s defining Reaganomics presidency. The cinematographic aesthetics provide an overt criticism of Ronald Reagan’s corporate tax reprieve in order to allow big corporations to further their investments and to allow for the influx and expansion of international business such as America’s liaison with Japanese motor companies—all of which widen the gaps between the haves and have nots. Extreme capitalism and commodification become the backbone for this dystopia. A bird’s-eye view sweeps through the polluted city engulfed by refinery clouds, navigating its way through spewed lighting from the refineries, streaks of neon city lights and the cacophony of the city. It is literally and metaphorically urbanely polluted. Scott’s dystopian world of an eroding city, filled with dark, wet alleys, prostitution, sleazy night clubs with blinding lights, graffiti on high tech telecommunication screens, and everyday thieving of flying transportation mobiles (called hovercrafts) not only capture a grim mood and atmosphere, but also the perilous realism stemming from the technological chaos and the densely populated geographical pockets (i.e., Chinatown) inhabited by the lower echelons of corporate laborers such as the Chinese eye engineer whom Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), a replicant, confronts regarding the whereabouts of his creator, Tyrell, Chinatown. The lonely and lowly Sebastian, Tyrell’s replicant designer who is also an underling of the big corporate hierarchy, lives in the cavernous Bradbury Building and finds solace in his creations, which are robots he has created, rather than humans. Critics hail Blade Runner to be the epitome of cyberpunk, a science fiction subgenre that explores the disparity between the social and cultural caste in the wake of a high-tech world with artificial intelligence and cybernetics. With a disparaging atmosphere, there is an explicit call for radical changes in social order—in this case, social economic, cultural, and moral order.

Among the dystopia is the civil strife between humans and the replicants. The film chronicles the anti-hero’s quest, Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), also known as a blade runner. He is hired to track down and expire the remaining four replicants (androids created by the Tyrell Corporation) who are illegally living on earth after being exploited for their dirty and perilous slave labor, a job in which humans refuse to do, that is, to remove nuclear waste. After their labor exploitation, a law is enacted to retire (kill) them as they are now considered useless commodity—obsolete in its purpose. Deckard, the blade runner, makes his way into the metropolitan underbelly of Los Angeles to carry out a quest that he, himself, cannot morally come into grips with. He is world weary, cynical, reluctant, and despondent about his job. Like Shelley’s monster, the replicants are considered a threat to society—more so to “social order by raising questions about the status of being” (Bukatman 49). Thus, Scott, and to a certain extent, Shelley, exposes the moral complexity behind this existential malady: should man’s drive for technological ambition culminating in a creation that harbors the basic human need to belong and survive in the human world such as Tyrell’s replicants and Victor’s monster be destroyed? Victor, like Tyrell, is adamant about expiring the replicants. However, Victor does it to save the world from the monster’s wretchedness—a crime he also has fully taken responsibility for as his creator. For Tyrell, the decision is based on a commoditized standpoint: he only creates them with a four-year expiration date, long enough to do what they are created to do. With the retirement law, “replicants are not permitted to compete with humans” (Bukataman 76). Consequently, “they are considered victims within the constructs of Western culture” (Bukataman 76). Moreover, the expiration date “operates as a fail-safe mechanism, protecting the human from its own obsolescence” (Buckatman 65). In essence, the retirement law secures humanity’s relevance.

Tyrell, unlike Victor Frankenstein who is wracked with guilt for creating a monster who kills, does not take any responsibility for the war between humans and replicants. He conveniently remains in his penthouse, away from the war zones. Instead, in the trenches is the noir antihero, Deckard, “the technologically enhanced detective/perceiver [who] sees, reads and explores an unsettled chaotic environment” (Buckatman 50). Deckard, as with all the noir antiheroes, is forced to make his own moral judgments in his confrontation about the authenticity of the human condition and the meaning of existence. Through this, death takes on new meaning for Deckard. This is clearly seen in a cathartic scene when Deckard battles with Roy Batty. Roy, aware of his own exploitation in a capitalistic world tells Deckard “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain. Time to die.” Roy’s death reduces him to a “has-been.” He becomes part of the decay, an old technological, outdated “existence.” Deckard’s final battle with Roy is a true testament of their mistreatment, which forces him to sympathize with the plight of replicants.

The civil war between human and artificial intelligence questions the very nature of what it means to be human as well as the moral responsibilities of playing God. The replicants, like Shelley’s monster, are “copies” of humans— at best, with the fundamentals of human emotions such as the need to survive. The human copy in Blade Runner, in particular, is taken further. Memories that stem from other humans are implanted in the replicants. Consequently, the distinction between what is authentic and inauthentic is blurred. Tyrell’s replicants go beyond human appearances: “the emotional life of the replicants clearly exists” and “they are not just physically and intellectually superior to humans” (Bukataman 77). They are ‘more human than humans,’ just as Tyrell proclaims” (Bukataman 77). This more than human quality consists of surpassing emotions, intelligence, and physical strength—all of which threaten humanity’s sense of relevance in an advancing technological world.

Unlike Tyrell, Victor questions his ambitions and narcissism, oscillating between self-deprecation and self-admiration for “birthing” an existence that has terrorized the world. He typifies the mad-scientist prototype with unbearable internal conflicts. He is partly in love with his creation in terms of being at awe with what he has created, a symbol of his scientific triumph. However, his creation is his enemy because he has obliterated his loved ones. He is considered a monumental horror—a living being so grand in size and scale, so domineering, and so threatening and physically repulsive. It is a haphazard copy of man—a parodic and hyperbolic human copy that stems from corpses—all of which make him revolting. For instance, “his yellow skin [has] scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath,” his complexion is “shriveled,” and his lips are described as “straight black” (Shelley 42). Consequently, the monster bemoans his misery as the rejected human. “You had endowed me with perceptions and passions and then cast me abroad an object for the scorn and horror of mankind” (Shelley 124). In spite of acts of good deeds, the monster is met with violence because of his hideousness. The creator and the created share a symbiotic relationship. Both are miserable in their existence; both are engrossed in guilt, self-pity, self-blame, and deflected blame. Through this, “Mary Shelley explores this matrix of reversibility and makes it the very hinge of her tale; she blurs the boundaries between the creature and the creator from the start, reversing posture and gaze in the laboratory and the bedroom” (Lanone 58). The interchangeable identity between monster and creator contributes to the strained relationship between father and son. Not only is the monster “the Gothic doppelganger” but he is also considered “the discarded son and self” (Lanone 58). “Nevertheless Frankenstein remains a tragic figure who invites a certain amount of sympathy for failed ambitions” (Smith 77). Similarly, the monster “to some degree be excused for his behavior” when he tells his creator the tragedy of his existence: “‘I am malicious because I am miserable; am I not shunned and hated by all mankind?’” (Smith 77) Therefore, their circumstances perpetuate a failed and cumbersome existence.

In contrast, Roy and Tyrell are each other’s foil—one being more superior than another in terms of social and human acceptance. Although Tyrell is the father/God who creates a son and then later rejects him, he suffers the consequences by dying literally from the hands of his prodigal son, Roy. When Roy Batty demands life beyond the four-year life span, he addresses Tyrell as father by saying “I want more life father.” In response, Tyrell only relishes in the supposed superiority of his design by telling him “The light that burns twice as bright burns for half as long, and you have burned so very, very brightly, Roy.” What Tyrell refuses to acknowledge is the ironic tragedy behind Roy’s “brightness” in which he laments during his fight with Deckard. For instance, he admits to living in fear—much like a slave. Symbolically, Tyrell’s thick bifocals draw attention to his flaws, that is, a vision impediment that carries literal and moral significance. Although Tyrell is a brilliant manufacturer in his creation of an “offspring” that he has envisioned to be great in its economic exploits, he lacks moral and humanistic foresight such as the replicants’ existential tragedy and feelings of betrayal as the rejected child. Because of this, Roy gauges his creator’s eyes—a symbolic action of disavowal towards his selfish creator/father.

Ex Machina

The creator/father dynamics and the disorder in the natural world takes on new meaning in Alex Garland’s 2014 release Ex Machina. Ex Machina is the science fiction film of the second millennia—which contrasts with Scott’s postmodern tenets in its critical commentary on human authenticity and capitalist control in Blade Runner. Garland’s dystopia is presented to be a disturbing Orwellian horror where cyberattacks are rampant and privacy has reached extinction. The intrusion is prompted by a ubiquitous digital world through the use of devices that links us to cyber portals—whether they are from hand held tablets, smart phones, laptops, large television screens, or computer screens. Garland’s dystopia has a different aesthetic compared to the futuristic chaos in Scott’s Blade Runner. He creates a very transparent, luminous, and glossy cinematography brimming with the tech gadgets’ fluorescent glow, bouncing off glass partitions and windows. The film’s opening sequence takes place in a tech office, an architectural open plan, a looking glass, a fish bowl, but with glass walls. The opening sequence is dialogue free—most shots consists of point of view webcam shots, overlooking a young data programmer Caleb (Domnall Gleeson) who is employed at a lucrative search engine company, Blue Book (the Google equivalent). The point of view shots reveal phone texts and email messages inviting Caleb to spend a week at the company’s CEO Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac). Caleb is part of the menagerie of coders enclosed in a see- through vessel. Their ghostly reflections of Caleb’s data programming cohorts are symbolically transparent figures—haunting, supernatural, and hyper-surreal. Symbolically, they are an eroding existence—as they are part of a big company cohort whose data are catalogued or recorded.

Thus, the ultimate crime in Ex Machina is the theft of humanity’s free will—as humanity is manipulated to perform, act, and behave in a certain way—much like Pavlovian subjects for big tech companies. How humanity interacts with their new devices—whether it is through the latest smart phones along with their invasive apps, the internet search engine, the newest tech features that keeps us virtually “connected” to the information provided by our device, and our searches—they become the tools for his next big creation. The late Apple giant and CEO Steve Job in his frenzied passion for the next innovative Apple product consist of dictating what people want. He asserts: “Some people say, ‘give the customers what they want.’ But that’s not my approach. Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do” (Isaacson 267). And this approach to consumerism and product commercialism connotes something more damaging than ever in the realm of human choice—that is, without choice. Even our smart phones make choices for us, predicting and mapping our next steps (based on our “recorded” routines) before we actually make them. This dictation of what humans want (a desire making us prone to addiction and dependence) gives companies the upper hand in “programming” human behaviors.

Thus, Ex Machina is an admonishment of the current milieu, particularly in its disconcerting and provocative criticism of our careless dependence (and addiction) to data producing and recording devices, making us vulnerable to the digital hacking of phones, computers, social media accounts, email, and every communicative device we use that links us to the cyber world. We rarely see face-to-face communication; we see face-to-screen communication. The sound of typing or the lull that stem from wired connections make up the film’s ambient score. Audible human dialogue is irrelevant in this world, which draws emphasis on human depersonalization, human detachment, and human isolation. The inputting and recording of data are ongoing, making big companies vulnerable to ransomware. Moreover, our digital footprint is the property of another conglomerate, used later for economic, political, and social exploitation and control. Interfacing is both intrusive and cerebrally “tapping.” More disturbingly, Ex Machina’s 2014 release foreshadows our political hacking of social media accounts (whether it is through Facebook, Instagram, or Google) and such cybercrime has led to the Russian collusion in the 2016 presidential election. Garland reflects and foreshadows the current 2014 technological milieu, as access to private information is not only in the hands of the inputter, but also in the hands of tech giants such as Mark Zuckerberg, the Facebook founder and CEO.

In Ex Machina, it is Nathan who owns humanity’s privacy through virtual theft. Nathan is the Orwellian mastermind, overseer, privacy invader and hacker, and most of all, exploiter and manipulator of the people he spies upon—including his own employees such as Caleb. The subject of Caleb’s private searches, his digital footprint and data, makes him vulnerable to a tech God’s manipulation and control, luring him to participate in his own ambitious study of his next creation, his female AI, Ava (Alicia Vikander). Because Nathan has access to Caleb’s Blue Book searches such as his pornography and data inquiries, Caleb has become the perfect candidate (and human component) for a “looking glass” science experiment with his latest female AI, Ava, who is also a physical prototype of Caleb’s ideal woman. Caleb is lonely (without a girlfriend), orphaned (whose parents died in a car crash), sensitive, and a hopeless romantic. As Nathan is able to lure him to his isolated home under the pretense of Caleb’s supposed exceptional skills as a decoder, he uses him as a science experiment to determine whether or not Ava can seduce him into performing certain acts, such as courting her romantically. The film’s ominous portrayal of data breach and its impact on human behavior provides a provocative and alarming examination of the erosion of free will due to our constant use of informational and communicative technology—the “looking glass effect.” Both he and Ava are living “through the looking glass”—literally and figuratively—as search engines provide insight to “how people think”—according to Nathan. The data of human beings make humanity vulnerable to being controlled by tech giants. In essence, humanity is following a script that is predetermined by a tech God. Thus, the disorder manifests in humans not having control over themselves.

Moreover, private data becomes sustenance for tech moguls’ creative ambitions such as Nathan Bateman’s AIs. The origins of Ava’s brain are from a cell phone hack, a shameless feat Nathan has no qualms boasting to Caleb: “Almost every cell phone has a microphone, a camera, and a means to transmit data. So I switched on all the mikes and cameras, across the entire fucking planet, and redirected the data through Blue Book.” The hack has gifted him “A limitless resource of facial and vocal interaction.” What is more frightening is that Nathan is immune to any criminal charges provided that he keeps his silence from other companies who have also intruded upon people’s private data. This code of silence among corporate conglomerates works conspiratorially—consequentially perpetuating the cycle of privacy, intrusion, theft and control. For Nathan, this becomes fodder in the creation of synthetic humans.

Ex Machina is also a hybrid science fiction genre with a tech-God mad scientist motif intertwined with elements of psychological thriller, especially in its depiction of humanity’s eroding free will due to being under constant surveillance. It is a conflict between who is in control and who is not. As a result, Garland presents a different type of dystopia. The world is in a state of paranoia, leading to interpersonal disconnectedness and, thereby resulting in alienation, isolation, artificial communication that is devoid of any live face-to-face communication. Like Tyrell who is somewhat protected from the dystopia, Nathan is away from any potential Orwellian hack. The threat of distrust and paranoia hovers above him like a “Big Brother” cloud, watching, recording, and analyzing every digital move. Therefore, Nathan lives in a remote habitat. His bachelor pad is nestled in the center of nature. It is constructed with glass walls or partitions, revealing the lush greenery of the outside world. The geographical region (filmed in Norway) is an ironic juxtaposition between nature and the artificial and simulated tech world. The aesthetics consist of an antiseptically clean (especially his underground laboratory), geometric dwelling—with no clutter. Camera set ups are ubiquitous; television monitors are readily available for review of previous surveillance recordings. The color palette consists of muted, monochromatic grays. Nathan, an alcohol guzzling, iron pumping, crude, hyper sexual, and expletive hurling tech mogul—becomes a foil to Caleb, the quiet, sensitive geeky tech nerd. His swanky bachelor pad consists of the latest sleek and modern tech gadgets such as doors that will only be read by identification cards. His home is the epitome of “guy land” or man cave (the research facility is a subterranean abode) with walls made of stone or concrete. If there is a power outage, the motor that operates the electronic doors, cameras, circuits, and so on are shut down in fear of someone hacking the “juice” (i.e., main electrical hub). He is isolated much like Victor Frankenstein in his work, which negatively affects the morale of his existence—a cloistered and paranoid genius—guarding himself from invaders and intruders who might tap into his secretive world, exposing his menacing ambitions.

What distinguishes Nathan from Victor Frankenstein is that Nathan is acutely aware that human existence has the potential to be unknowingly subjected to a mere science experiment provided that their private lives are up for grabs. And such distrust is contagious. It is no wonder that Caleb begins to doubt the authenticity of his human existence during his Turing test experiment with Ava. He cuts himself to see whether he bleeds to convince himself of it. While being under constant surveillance and under Nathan’s strict contractual command to remain cloistered and not have any contact with the outside world especially in regards to his experiments with Ava, there is a suspicion of being manipulated (more so in the form of puppetry) by his boss who also has a tendency to be bullying and oppressive since he pulls the strings in regards to the Turing test with Ava. From this, Caleb feels the uncertainty of his existence, especially being around AIs, and decides to cut himself to see whether he bleeds.

Therefore, the real monster in Ex Machina is not the AIs Nathan has created, who will eventually revolt against him, it is the high-tech surveillance (courtesy of a mad scientist) and the information gathered and used to control other humans into becoming testing tools for the latest technological inventions. This can be perceived as apocalyptic for humans. Nathan shares this fear to Caleb in his prediction of AIs surpassing human capability, monsters that he, even a genius himself, cannot control: “ One day the AIs are going to look back on us the same way we look at fossil skeletons on the plains of Africa. An upright ape living in dust with crude language and tools, all set for extinction.” The AIs are the new technology, placing humans under their surveillance, studying their every move, and seeing what motivates them to act a certain way. In turn, Caleb quotes atom bomb creator, Oppenheimer, in response to Nathan’s fear of human extinction. Oppenheimer refers to himself as “death, the destroyer of worlds.” This begs the question: is it a man’s world that is really destroyed? And will this “new world” consist of female dominants only?

God, The Pygmalion Myth, and the Female Simulacrum

The mad scientist who aspires to play God takes on a whole new different meaning when it comes to the Pygmalion myth, especially in the science fiction genre. The desire to create the perfect woman becomes the crux of the Pygmalion myth. Women’s studies historian and film critic Julie Wosk in her work My Fair Ladies: Female Robots, Android, and other Artificial Eyes asserts “Men have long been fascinated by the idea of creating a simulated woman that miraculously comes alive, a beautiful facsimile female who is the answers to all their dreams and desires” (9). Wosk makes strong parallels to the Pygmalion archetype by making references to Roman poet Ovid in The Metamorphosis in order to illustrate man’s desire to create the “perfect” woman. Pygmalion, a marble sculptor, was unsatisfied with women. “He was ‘dismayed by the numerous defects of character Nature had given the feminine spirit’ and, therefore, “sculpted a beautiful ivory image of a perfect woman” who ends up becoming alive after praying to Venus, the goddess of love,” to turn the ivory sculpture “into a flesh-and-blood female later known as Galatea” (Wosk 9). When he caresses her and kisses her, “the ivory softens like wax,” prompting Pygmalion to exclaim: “’[She’s] alive!’” (Ovid 10.232) This becomes an iconic refrain in science fiction AI films—courtesy of the 1935 Universal production of The Bride of Frankenstein by James Whale. But there is a misogynistic and sexist ideology that is perpetuated behind the Pygmalion myth. Through Pygmalion’s “surveillance” of women, “Pygmalion had seen these women spend/Their days in wickedness, and horrified/At all the countless vices nature gives/To womankind” As a result, Pygmalion “lived celibate and long lacked the companionship of married love” (Ovid 10.232). As a result, he creates a female simulacrum “with marvelous triumphant artistry” and “his masterwork fired him with love” (Ovid 10.232).

In contrast, human creation in Frankenstein originates from a flawed mindset. As “scientific investigations function as metaphors about creativity and the imagination” in which Victor Frankenstein “strives after beauty,” the ambitious feat culminates in “the creation of ugliness [particularly from a visual standpoint] because the imagination is diseased and feverish” (Smith 81). In consequence, the creature, “can therefore be perceived not just of science” but also “of a disoriented imagination” when it comes to his birth and creation (Smith 81). In a Pygmalion creation, the feminizing of a creation starts with the intent of beauty (aesthetics) that stems from a man’s fantasy, echoing the sexist gender norms of the current milieu. In addition, “the Pygmalion myth remains a potent fantasy in stories” in which “young men fantasize about using their skills in science and technology to create a perfect simulated woman, a female that they envision as innocent and virginal yet will be an answer to all their needs” (Wosk 29). And the power of the male imagination within a mad scientist context is prompted by his own needs that are similar to Pygmalion, that is, his yearn for a docile woman who will fill the void—as both accomplished scientist and a man with the “perfect” female companion.

A feminist reading of Frankenstein lends itself to a metaphorical examination of nature as being feminine according to Anne K. Meller in her work “Frankenstein: A Feminist Critique of Science.” She claims that scientific ambitions are considered “exclusively masculine” and “the triumph over a feminized nature is . . . implied by how Frankenstein, in creating life, has eradicated the role of women in giving birth, which explains why the women in the novel seem so sexless (and why he wishes to destroy the potential mate he is making for the creature” (Smith 78). The mad scientist usurps women’s natural birthing abilities. Similarly, in Ex Machina, Nathan shows off his technological ingenuity in the “birth” of his ideal woman. According to New York Times film critic Manhola Dargis, she comes up with the mad scientist CEO prototype:

Ex Machina is itself a smart, sleek movie about men and the machines they make, but it’s also about men and the women they dream up. That makes it a creation story, except instead of God repurposing a rib, the story here involves a Supreme Being who has built an A.I., using a fortune he’s made from a search engine called Blue Book.

And from this, Nathan can further show off his masculinity through acts of chauvinism and misogyny. He relishes in his control over his AI woman—especially in his sexual prowess. After all, he can afford to do whatever he wants in the world he creates—both literally and figuratively. This is exemplified in his interactions with his fembot, Kyoto (Sonoya Mizuno), his mute, scantily clad servant. She is also considered “the schizoid android,” which possess “qualities of being both literally a machine—she is often a robot/android” and “acts machine-like: computational, emotionally shut off, and logical” (Flisfeder 122). She roams the corridors like a ghostly apparition. In zombie-like fashion, she will do, without question, what he commands. On cue, she will dance with him. She is also readily available for sex. In this creator and created dynamics, Nathan is the master and Kyoto is a cipher who is unthinking and just doing. This explains her ghostly apparition or zombie-like mannerisms, lurking around the compound, observing and ready to be told what to do. Such docility is Nathan’s ultimate triumph over the feminine nature, revealing his contempt for femininity by reducing it to superficial means. In Kyoto’s case, she is the “pleasure model” and the mechanical blow up doll with domestic duties. He tells Caleb that she is built precisely for that function: “I strip out the higher functions. Then reprogram her to help around the house and be fucking awesome in bed.”

According to Nathan, a sexual dimension in an AI is necessary for consciousness. Although he agrees with Caleb who declares that “sexuality is an evolutionary reproductive need,” Nathan also relishes in the pleasure aspect of sexuality by telling him if “you’re going to exist, why not enjoy [sexuality]?” This reveals his myopic vision of the other sex. Therefore, it is “bad enough that Nathan wants to play God at all, worse still that he longs to re-create femininity through circuitry and artificial flesh. His vision of women seems shaped by lad magazines, video games aimed at eternal teenagers, and the most juvenile “adult” science fiction and fantasy” (Seitz). Kyoto is the exotic Japanese fembot. Her creation resembles the Pygmalion archetype that corresponds to the current female ideal. The simulated woman “would be echoed over the centuries ahead in cultural images revealing men’s enduring fantasy about fabricating an ideal female” (Wosk 9). And when Nathan creates Ava, he makes sure it represents the “type” of woman Caleb is attracted to, which eventually makes him the perfect “control” cohort in the Turing Test with Ava. In turn, Nathan grants Caleb permission to give her pleasure because she is “anatomically complete,” equipping her with a “vaginal” cavity with pleasure sensors if stimulated correctly. She will also be Caleb’s pleasure model.

Because of the exploitation of the female AI, the mad scientist archetype (as God the creator) is tightly connected to moral corruption spurred by vanity and self-aggrandizement. Frankenstein creates his first monster out of ambition, obsession, and narcissism—not companionship—unlike Pygmalion. According to Frankenstein, his creation is to elevate man as a God. “I will pioneer a new way, explore unknown powers, and unfold to the world the deepest mysteries of creation” (Shelley 33). But Victor Frankenstein fails as the Christian model of a good God, that is, a forgiving and loving God. His Godly skills wreaks havoc on his life and family when he cannot control his creation and, therefore, vows to kills him. At the graves of his wife, Elizabeth, and his brother, William, both of whom the monster has killed, Frankenstein vows to carry out “dear revenge” and summons “the spirits of the death” and “wandering minsters of vengeance to aid and conduct me in my work” (Shelley 186). Victor becomes an angry God motivated by vengeance.

Furthermore, both the Pygmalion archetype and the mad scientist archetype (as an ambitious God) have immoral tendencies, especially when it comes to a mechanical female equipped with consciousness. Caleb makes a disturbing declaration of man’s scientific ability: “If you’ve created a conscious machine, it’s not the history of man. That’s the history of gods.” The mad scientists are notorious for creating women that are expendable: they give life and ruthlessly take life away whenever they please. Nathan’s graveyard of defunct cyborgs is a testament to his tyrannical godly nature. This is also revealed in Caleb’s disturbing discovery of CCTV files with different names of female cyborgs—one video shows an AI engaged in mechanical rocking movements (as if malfunctioned), another video shows one limp and unmoving, the last video, a file labeled “Jade,” is a recording of Jade (another AI) that shows Nathan’s AI exploitation through imprisonment. In the inaudible recording, he sees a nude AI Asian model, the exotic erotica, banging against the class partition after arguing with Nathan. Her arms crack open and carbon fibers are released like course hair. What adds to Nathan’s tyranny is that he makes all of his female AIs, especially those who are rebellious and unruly, an ex machine. His harem is too threatening for him, especially when they rebel. The defunct and broken AIs make up Nathan’s underground laboratory, which, in actuality, is a graveyard of disembodied AIs. Scattered arms, faces, and torsos are ubiquitous in his research facility. They are literal fragments of the “imperfect” woman, that is, too uncontrollable or unruly for their creator.

God having the “upper hand” when it comes to the life span of an AI is exemplified in Ava’s disposability—much like her predecessors. This goes back to the Pygmalion intent—the belief that the perfect woman must remain in its most “basic” form (i.e., an object of beauty). When Caleb talks to Nathan about a new model, Nathan reveals his plan to get rid of the old one, in this case, Ava, and recycle her physical body to create another AI that will be considered “the real breakthrough.” Ava is only a derivative model of a Version 6. Nathan plans to “unpack the data” and “add the new routines” he has been working on. To achieve this, he will be “partially formatting” Ava’s system, removing all the memories Ava has accrued, leaving only the body. He will keep Ava’s body because he claims that “it is a good one” just as he has done with Kyoko, his fembot. This “blank slate” for Ava will erase her “relationship” with another human. Her astute understanding of human “micro expressions” are tallied in her memory, providing her the ability to determine her next move when it comes to interacting with a human. Thus, to remove her memory is to cripple her ability to build upon the knowledge she had before. Ava needs her previous knowledge, which will help dictate her next move in getting her human counterpart to respond to her actions. For instance, she knows how to get Caleb to sympathize with her situation and eventually become the prince who will save her. Ava’s ability to manipulate human emotions makes her the best product to date. In particular, her most intimidating features are her sexuality and female intuition in which Nathan acknowledges. This is ascertained at the end of the test in which Nathan tells Caleb that Ava has demonstrated true AI: “Ava was a mouse in a mousetrap. And I gave her one way out. To escape, she would have to use imagination, sexuality, self-awareness, empathy, manipulation—and she did. If that isn’t AI, what the fuck is?”

Nathan’s tyrannical nature as a scientist is motivated by his need to oppress his female AIs—regardless of their sophisticated abilities. For Nathan, it is imperative that he still has control over his “women.” In spite of this, Ava is able to be intuitive about her fate, telling Caleb that Nathan is a liar, pitting both men against one another. She is astute enough to ask Caleb about her fate: “Do you think I might be switched off? Because I don’t function as well as I am supposed to?” Because of Ava’s threatening nature, Ava will be among the various “bones” housed in Nathan’s laboratory or among the AIs kept in closets, manually turned off, defunct, expired. But the real test is not whether she fails to function as well as Nathan creates her to be, the real test is to see whether she functions too well in which her creator, Nathan, cannot handle. When it comes to the issue of gender and the science fiction genre, there “has been a long tradition in sf where a certain ‘female’ character has had central role –in stories where the traditional engendered hierarchies of society are overturned and where ‘women rule’” and also referred to the “woman dominant” (Merrick 242). Ava is the woman dominant who learns how to manipulate both men to escape. She is the genius in a deux ex machine, a Greek expression that reverts back to classical Greek drama conventions in which a machine or crane is used to hover over a stage carrying a god, which is used to resolve a conflict that appears impossible. Ava is the masterful God attached to the machine. Nathan’s godly nature is his ability to create a female machinery—and he is not entirely proud of it because his inventions pose as a threat to man. Both human and machine are caught in a Darwinistic battle—but in Ex Machina, it is the battle between sexual wills, that is, the God of machinery (man) versus the God of intuition (woman) or female consciousness.

Blade Runner: Pygmalion and Mad Scientist Hybridization

In Blade Runner, the Pygmalion and mad scientist motifs also lend themselves to moral corruptions, especially in the exploitation of females. For the female AIs Roy creates, they are used as pleasure dolls (prostitution), beauty props, or other forms of female abuse that can also be considered enslavement, more specifically for the needs and pleasure of men. When Deckard reviews Zora’s AI profile, she was used as a ruthless killer or murderess during the outer-world battle. She is lauded for killing people in groups. She is built with strong womanly features with stacked breasts and rippling lean muscles. She is a marbled Galatea (the name of Pygmalion’s sculpted lover who comes to life), almost indestructible in her form because she is considered to be Amazonian. Zora is referred to as “beauty and beast”–a paradoxical nature of woman. Her exploitation continues on Earth. In essence, Zora is a sex object, that is, one to-be-looked-at (in Mulvey’s terms) by men. Zora resides and works in the city’s sleaziest underbelly as an exotic stripper in a nightclub. Her exoticism is accentuated with an artificial snake that rests above her shoulders like a fox stool and she adorns herself with glittery snake scales. Her serpent-like image complements her beauty and beast moniker. Her death is hyper-violent and visually stylized. Deckard chases her through the crowded streets and fires multiple gunshots. When the bullets penetrate her, she loses her balance and runs into a shop with glass walls. She bleeds profusely not only from the multiple gunshot wounds but also from the pieces of glass that pierce her skin. Her corpse blends among the partially naked mannequins from the store display. Her death culminates into a violent freak show. It is hemorrhagic and blindingly reflective as it is exacerbated with flashing neon and fluorescent lights, making her death surreal and nightmarish.

The other sexualized AI is Pris. Like Zora, she, too, can be considered “apt models for future videogame avatars” because they can be both “formidable and seductive” (Wosk 120). Pris was specifically created to be the typical prostitute or “basic pleasure model” whose job is “to service men in military clubs in the ‘Outer-colonies’” (Wosk 120). On earth, she is the lost and fearful runaway until she meets Sebastian, a biogenetic engineer, and reunites with Roy. She, too, is strong and is able to put up a good fight with Deckard. Through these exaggerated or hyperbolic “womanness” there is an essence of dominion over the man, in which Deckard struggles with. Zora is able to throw a good punch and outrun from her enemy. “In the absence of fixed identities [in a postmodern world], the fixity of identity politics is also abandoned;” and “if gender roles are variable, fluid, and multiple, they lend themselves to oppositional strategies, principally in the form of parodic subversions” (Sheehan 34). Symbolically, Pris makes an eerie attempt to blend in with the rest of Sebastian’s mechanical dolls. Furthermore, “The mechanical females that seemed to magically come alive were actually part of a long technological history of articulated dolls and mechanical automatons or self-moving, mechanical humanoid figures—figures that were shaped by cultural conceptions of femininity and women’s social roles” (Wosk 34). Pris is, in a sense, Barbie doll-like, or rather a parody of it with wiry blond hair and combative traits. This is illustrated when her long, shapely Barbie legs are used to grip Deckard into a headlock and successfully throw his body around. But Deckard is a man armed with a pistol and has the advantage. He is able to violently kill both Pris and Zora with multiple shots.

To compare the deaths of both Pris and Zora, they are more gruesome and painful than the death of Leon and Roy. Pris, reverting back to the “living doll” caricature, is shot in the stomach multiple times, causing her body to convulse violently while she lets out a screeching, electrical sound, amplifying the destruction of her mechanical entrails. Roy dies “naturally” as his time was up, and Leon dies from a single gunshot wound from Rachel. Both Zora and Pris are far from the docile fembots, there is an explicit misogyny towards the female replicants because they are treated as the fatales. In actuality, they are considered the “woman dominant” as opposed to the traditional sense of the conventional femme fatale whose function is to “manipulate,” “to double-cross or occasionally to domesticate –the male lead” (Schatz 114). Nor were they “good-bad sirens,” “black widows,” or “good-bad sirens” (Schatz 114). They are brutally killed because their wits are superior enough to fight back physically—more so than their male counterparts. The zealous need to “expire” both Pris and Zora is a testament to man feeling threatened by a stronger woman. Deckard is hired to keep the so-called fatales at bay and to keep women in place—as the weaker sex. To lure Zora in his trap he ironically pretends to be an advocate in protecting women from sexual exploitation.

The “woman dominant” takes on a different meaning when it comes to Rachel who is an interesting dichotomy of a woman dominant and the Galatea archetype—the Pygmalion female invention “who embodies the innocent, naïve, self-sacrificing female” (Wosk 14). And from a Postmodern lens, Rachel’s is a copy of the 1940s female noir prototype. To be more specific, she is a futuristic version of a Joan Crawford Mildred Pierce mash-up—ruby lips, rolled bangs, thick shoulder pads, and a pencil skirt—a female simulacrum, “[who] pastiches the style of the others” (Butler 141). She represents the 1940s beautiful secretary or assistant to the powerfully rich Tyrell. At first, Deckard, is disdainful of her by reducing her to a pretty pleasure model. In his drunken stupor, he asks her to join him for a drink at a dirty and sleazy bar. She rejects him by telling him “it’s not my kind of place.” When she is determined to leave his apartment, he seduces her. He then gives her new memories by commanding her to kiss him and to put his arms around her body. Like a Galatea, Deckard “sculpts” her into romance.

You buy levitra professional need to do some research about the birth control hormone medications. It offers viagra online uk effective cure for weakness, PE and impotence. Nevertheless, with so many effective treatments available these days, you can easily find online dealers that are selling counterfeit prescription medication at low prices, so be about on line levitra on line levitra vigilant. Before to taking notify your doctor if any sexual problem keeps happening. viagra sample online

As for the typical immoral scientist and God, Tyrell creates her (or rather molds her) for mere experimental purposes and of course, to ascertain the highpoint of his technological and scientific achievements. Rachel is a Nexus 7, the generation after the six-generation replicants such as Roy, Leon, Pris, and Zora. Rachel has no clue she is a replicant and because of this, she is willing to put herself in precarious situations. For instance, with the urging of her creator and master, Tyrell, she willingly becomes the subject of the Voigt-Kampff test, a test used to determine whether a human is artificial. The test consists of a series of empathy questions that will eventually elicit a physical response such as capillary dilation (i.e., the blush response), heart rate increase, and involuntary dilation of the iris and fluctuation of the pupil. (After a few years, the Nexus 6 replicants are able to develop their own emotional responses: hate, fear, angry, envy.) The Voigt-Kampff test is also analogous to the Turing Test.

Like Ava in Ex Machina, Rachel is a rat in a lab. She is subjected to a Turing Test equivalent. On the other hand, in Blade Runner, Tyrell is able to see how “impressive” his latest creation is when Deckard administers the empathy test. He tells Deckard “I want to see a negative before I could provide you a positive.” She is a Nexus 7, the best AI to date. Because she is the latest creation, it took Deckard nearly a hundred questions to determine whether she is a replicant. Normally, it would take approximately thirty questions to make the determination. Tyrell is not ashamed to relish in the technological feat. Rachel has the “gift” of memories, “used not to control [her], but to help [her] structure [her] relationship to [her] emotional responses” (Flisbeder 130). But the use of photographs, such as the photograph of Rachel and her “mother,” and the artificial memories from Tyrell’s niece as part of Rachel’s programming, question the very essence of what it means to be human. Postmodern theorist Matthew Flisfeder asserts: “If memories can be implanted—if emotions can be replicated in androids and artificial intelligence—what then is truly “human” about humans? Is there an essence to our humanity?” (130). She is the “perfect simulacrum because she does not imitate human emotions but rather simulates them, undoing the distinction between a real human being and a bad copy” (Constable 49). There is no distinction between the authentic and inauthentic. With all of the fabrications Tyrell implants in Rachel, he fails to answer the “now what?” question, especially after his creation has developed an emotional response to her artificiality and the sad emotions that comes with the painful knowledge that she is a false human with false memories. Once those emotions are unleashed, Tyrell does not know how to control them. Instead, he rejects her in spite of the fact that he takes pride in the fact that she is the zenith of his invention—and the exemplary model that fits his business motto “more human than human.”

Tyrell also harbors the same rejection that mad scientists do when their creation has emotions that cannot be easily reconciled because of the very “nature” of their artificiality. “The NEXUS 6 replicants are manufactured like any other commodity. They are themselves commodities, but are they not also slaves? This last point puts not only their“humanity,” but also our own into question” (Flisbeder 158). The “you’re still not one of us” supposedly justifies the mistreatment of AIs—in spite of their ability to feel the pain of rejection—all of which make them more human than human. Ironically, humans become inhumane and their exploitations, selfishness, and barbarism make them devoid of human pathos that are definably human. The rejection is also a cathartic moment between the creator and the created in Shelley’s Frankenstein. The monster cries out to his father by telling him “You had endowed me with perceptions and passions and then cast me abroad an object for the scorn and horror of mankind” (Shelley 124). Both Rachel and the monster demonstrate the human pathos of wanting to be accepted as human and surviving the world that they are placed in. Rachel does not have an opportunity to cry out to her father. Instead she cries out to her interrogator, Deckard, who coldly tells her that the memories that are implanted in her are from Tyrell’s niece. The photograph of mother and herself as a child is a fabrication. As a replicant, there is no choice for her but to be a fugitive, especially when she abandons her creator. And consequently, Gaff (Edward James Olmos) adds her to the count of replicants Deckard must expire.

In spite of her synthetic existence, Rachel does demonstrate a higher consciousness—in a sophisticated and intuitive moral sense. She comes to recognize this when she tells Deckard “I am not in the business. I am the business.” Therefore, she, too, is disposable commodity (an “experiment” as Tyrell mentions soon after the Voigt-Kampff Test) just like the rest of the replicants—and Rachel is astutely aware of this. Rachel’s intuitiveness makes her more insightful than Deckard in spite of the fact that she is considered the femme fatale. She exposes corporate corruption and exploitation. She asks him whether he has ever taken the test himself and whether has he retired a replicant by mistake. She gives him a test of moral inattention or carelessness, questioning his practice of the law and whether it actually has moral clout. Because of this, Rachel has a moral compass and is able to redirect Deckard’s moral compass later. She has the insight and foresight when it comes to laws that are flawed, contradictory, and unjust. “If the world of Blade Runner is cruel and immoral, portrayed through noir conventions, it is the sci-fi conventions that bring forth a conflicting (perhaps even contradictory) morality” (Flisbeder 107). More specifically, it is Rachel’s questioning of the law that points out this contradiction. It is Rachel who initially exposes a flawed and corrupt law that divides classes, that perpetuates female exploitation, and allows for murder of an existence that is no different than humans—aside from human conception. This becomes a telling moment for Deckard as well as he later comes to learn of his own synthetic existence—as he, too, is exploited into slave labor. His job as a blade runner is to put himself in peril and to roam the dirty streets of Los Angeles, coldly taking away the lives of those who are “more human than human” with memories and pathos that are no different than the average human.

Because of this, she sets a new precedence for the femme fatale prototype in a noir narrative—one that is subversive. Rachel is able to reconstruct the moral law by taking the laws into her own hands. Self-preservation eventually becomes a priority for her—and to achieve this, she wins over Deckard’s sympathy but not through the damsel in distress mentality, but by saving Deckard’s life—which “evens out” the playing field between fugitive and lawman. As a result, he promises not to retire her. Rachel’s killing of Leon works along the lines of quid pro quo—she saves Deckard merely to save herself. She is considered an outlaw after fleeing from her creator. Most importantly, she leaves with Deckard as his equal—and not as his damsel. Both are replicants and both have saved each other. While Deckard is the flawed lawman, Rachel is the moralistically driven outlaw—a crusader for her own beliefs.

The Femme Fatale and the “Male Gaze” versus the “Looking Glass” (as a Mirror to What Men Wants)

The characteristics of a femme fatale are usually straightforward. Classic noir icon Humphrey Bogart in John Huston’s 1941 Maltese Falcon tells his love interest, Brigid O’Shaughnessy (Mary Astor), who was responsible for his partner’s death, Miles, that justice must be served in spite of the fact that he will be the hapless lover. “I’ll have some rotten nights after I’ve sent you over, but that will pass.” In the classic noir, the femme fatale is evil. It is clear that O’Shaughnessy is morally wrong and must be incarcerated. She can no longer be free to live in the outside world. And like most fatales, she is not the ideal lover because she is capable of betrayal. He tells her: I’ve no earthly reason to think I can trust you. If I do this and get away with it, you’ll have something on me…that you can use whenever you want to. Since I’ve got something on you . . . I hope you wouldn’t put a hole in me someday.” He forgoes love in order to uphold the law by telling her: “Sure I love you, but that’s beside the point.” When it comes to a femme fatale, there is no moral ambiguity and most importantly, moral contradiction.

But what initially lures Sam Spade to O’Shaughnessy is that she is considered “a knockout.” As a result, he buys into her damsel in distress sentiments, which eventually lures him into a web of greed and betrayal. As Sam Spade’s ogles the “knock out” O’Shaughnessy when he first meets her, he is explicitly objectifying her through his gaze and such a pleasure cost him the death of his partner. Because she is the epitome of a femme fatale in a noir using sex to thwart Sam Spade’s efforts to carry out the law, he ends up as the hapless lover and realizes that sexual attraction comes with a price.